A woman's (unpaid) work is never done

In 2020, women are still vastly overrepresented in the unpaid economy. But, what are the costs of this unpaid work on our financial security, and how can we redesign a more just and equitable system going forward?

Picture this: you’re in the middle of a job interview, you’ve outlined your experience and rattled off a bunch of great examples that showcase your skills. Things are going well. As the conversation wraps up, the interviewer says: “We should also mention, you will only be paid for 35.6% of the work you do”.

*Looks for nearest exit*

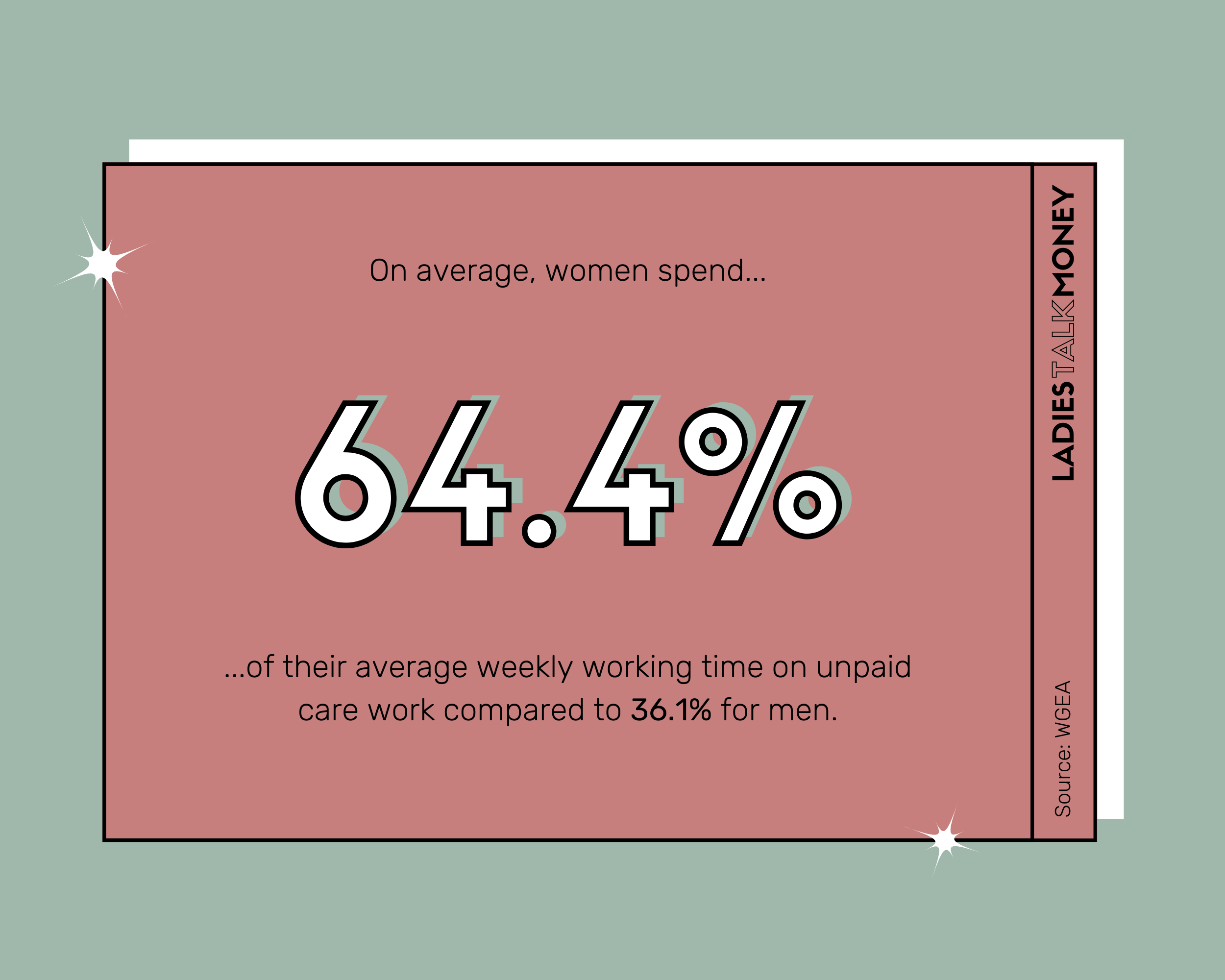

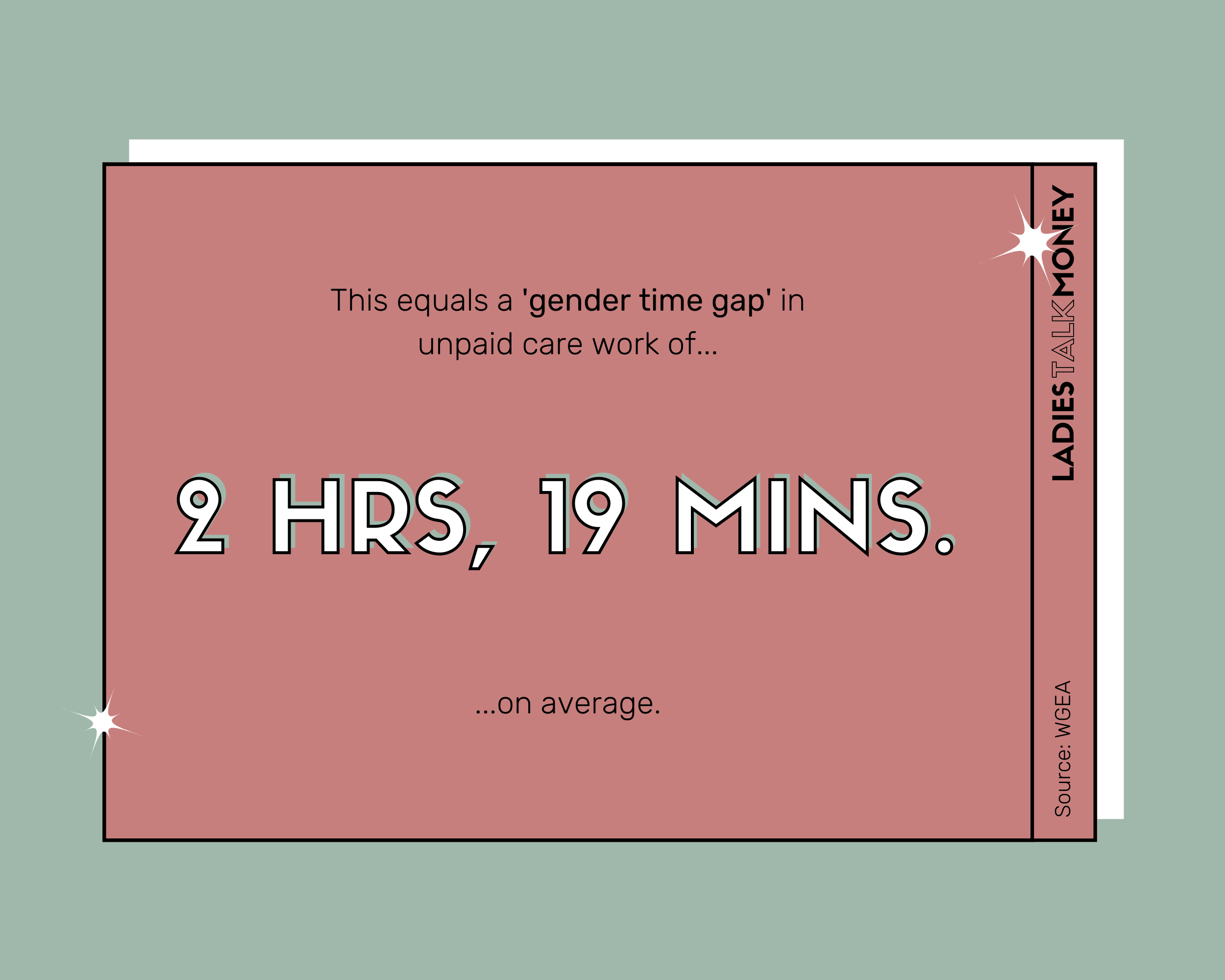

Lady, we wish this was a joke. That figure (the other 64.4%) represents the portion of unpaid work completed by women each and every week in this country (which is nearly double men’s average contribution and only getting worse during the pandemic). And, in case you haven’t already spat your tea out, you better put down the mug because the value of unpaid care work to Australia’s economy is estimated to be $650.1 billion a year. Yes, billion.

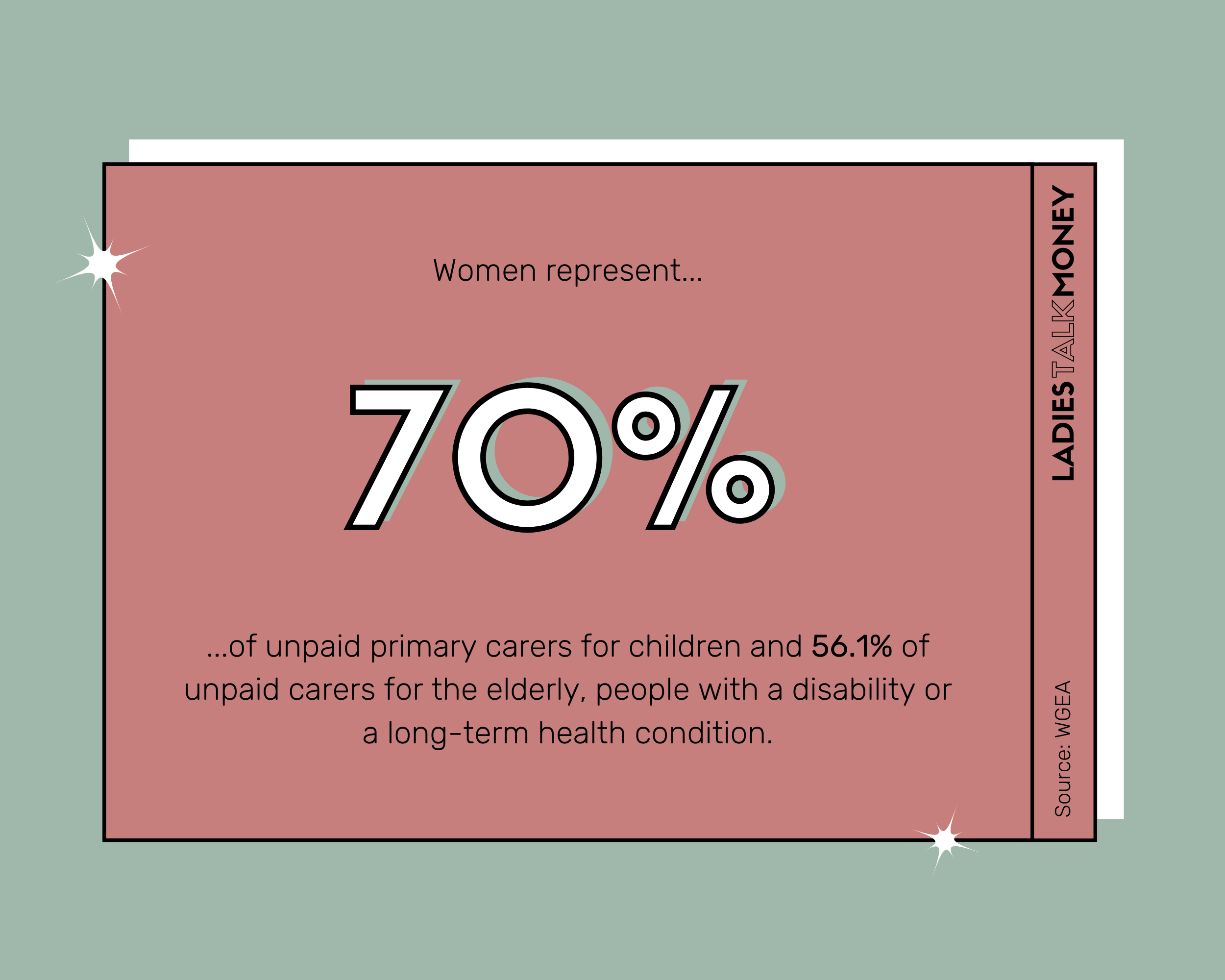

There’s no formal job description or any kind of salary, but unpaid care work is adding enormous value to our economy and society. And the worst bit? Women are overwhelmingly footing the bill for it (with 72% of all unpaid work in Australia completed by women), and some women more than others.

Harmful gender stereotypes have a lot to answer for in reinforcing the exploitation of women in the context of unpaid care work. While society continues to label us as ‘caregivers’ and the ‘natural’ doers of this work, the patriarchy continues to lump the burden of responsibility on us. To be QUITE honest, the value and extent of unpaid work in this country has been hidden by those who benefit most from it for far too long. Why? Because that unpaid care work enables society to continue functioning and, if we had to pay for it in cold-hard cash, we’d be in for a rude awakening.

Mark our words: the current reality relies on the systemic exploitation of women. Keeping care work off the books props up a system to keep (white) men in power and the rest of us too tired, busy, and locked up to do anything about it. As a society, we need to put an end to that. And it starts by talking about this invisible work of women, bringing it into the light and quantifying it in ways that those in power can understand.

The value of unpaid work

Unpaid work covers everything from volunteering to domestic household tasks and caring responsibilities. This includes cooking and cleaning, caring for people and raising children. And don’t even get us started on emotional labour and the mental load of managing it all...

This work takes time and energy, and sometimes even costs money, and women are disproportionately doing more of it than men. This ‘second shift’ reduces women’s capacity to participate fully in paid employment. In fact, there’s a clear link between how much unpaid work we do and the conditions of our employment.

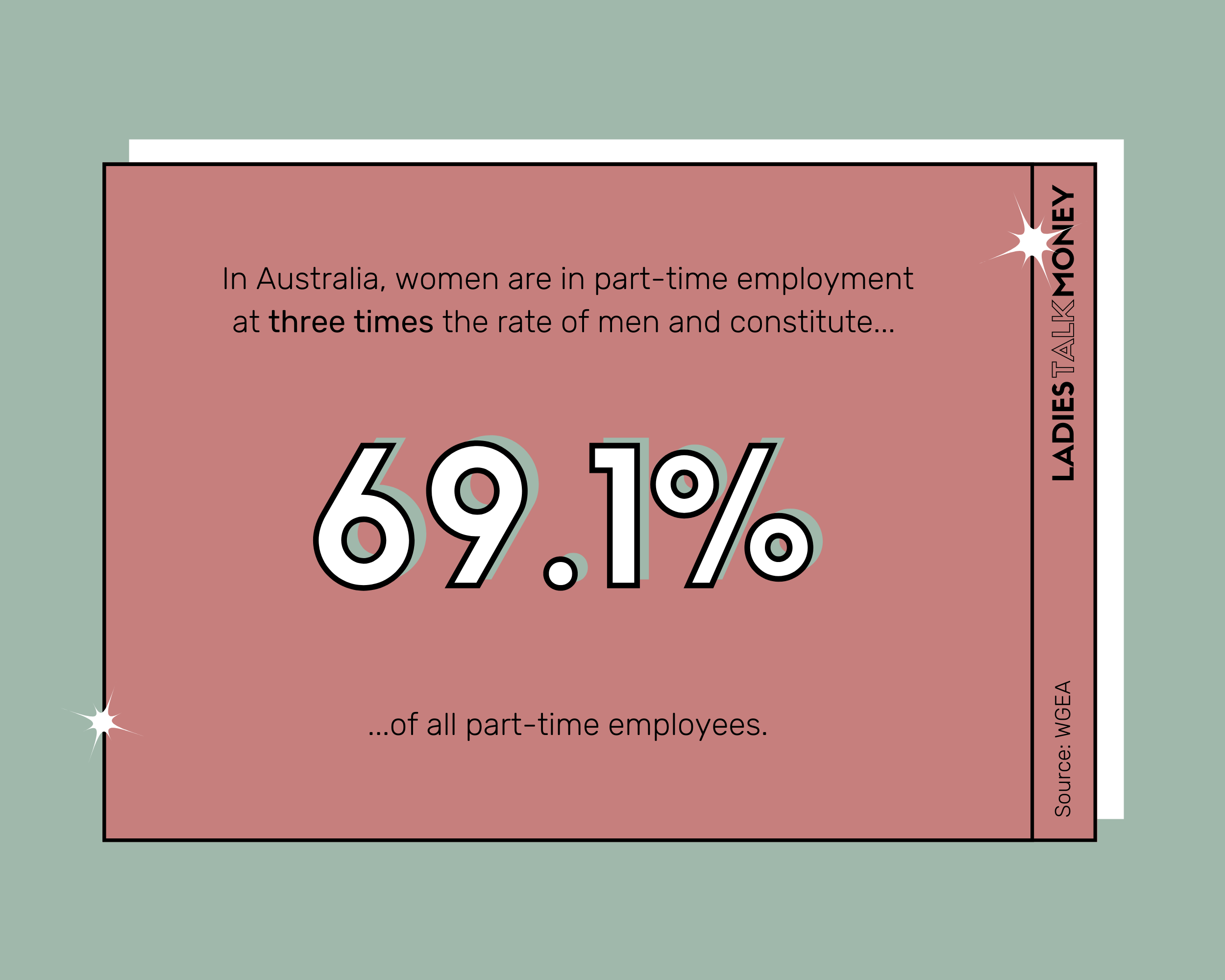

It won’t surprise you to know that women are 3x more likely to be in part-time employment than men. This means lower levels of income, less career growth and limited promotion opportunities. The result? Less cash in our pockets now (and in the years to come) and bags under our eyes that we are then shamed into paying exorbitant amounts of money to ‘fix’ with miracle creams (we told you not to get us started!).

Just because we’re not paid for these extra hours of labour doesn’t mean this work isn’t making a substantial contribution to our economy. To put this in perspective, unpaid care work generates the equivalent of 50.6% of Australia’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP). The thing is: unpaid care work isn’t factored in when calculating our GDP. Wonder why?

And when it comes to unpaid care work, women are overwhelming doing the lion’s share of that too. In fact, unpaid childcare is the Australian economy’s single largest sector (triple the size of the financial and insurance services industry). Indeed, better access to childcare = $10.3 bn increase in GDP by 2050 (PwC, 2014), which is why we should all be campaigning to Make It Free.

Putting a dollar sign on this work isn’t often done, but it should be. To set us on the path towards systemic change, we need to use the language of economists and policymakers to quantify the contribution of this work in metrics they can understand.

But at the same time, we need to work towards crafting a new narrative that challenges the systems that have exploited women’s unpaid care work for the benefit of those in power. In order to acknowledge the value of this work and to foster an equitable split of unpaid work between men and women, we need to move beyond economic measures and reframe care work as responsibilities we all need to share.

And who foots the bill?

Spoiler alert: women. But, we don’t carry this burden equally.

The impacts of unpaid care work differ depending on our economic situation. For those in higher socioeconomic brackets, the amount of unpaid care work often decreases as options such as paying for the costs of childcare become more feasible. But for others, lower-income means more unpaid work (and subsequently more time out of paid employment too). It’s a downward spiral that those in power don’t want us to break.

But there’s still more nuance to the issue of unpaid work. And depending on what our story looks like, we feel the impacts very differently.

For those of us with children, it’s estimated that raising kids accounts for a 17% loss in our lifetime wages. And taking parental leave? That causes another significant hit to our finances, with Aussie mums who returned to work 12 months postpartum seeing an average 7% wage penalty (increasing to 12% the year after). This is a consequence of our wages stagnating, with this ‘motherhood penalty’ increasing in line with the length of time we take off.

For those of us caring for ageing parents (a role that also disproportionately falls to women), the challenges of renegotiating the relationship we have with our parents can be complex and deeply emotional, whether that’s making the decision to move our elderly parents into aged care facilities or assisting with their day-to-day needs such as restocking groceries and helping with household chores. And for many of us, this is work we’ve been doing for as long as we can remember, whether that be caring for elders or others in our kinship networks. It also affects our ability to work, earn, and take care of ourselves.

For those of us who volunteer or assist in community work, this brings another set of unpaid responsibilities to juggle alongside paid employment and unpaid care work. In fact, the number of Australians choosing to volunteer for not-for-profit organisations is on the decline (dipping from 34% in 2010 to 31% in 2014, according to the ABS). With mounting responsibilities and less time available to contribute, this is a juggling act fewer Australians are able to take part in.

For those of us working part-time, casually or as a freelancer, we’re burdened with the costs too. Working in financially precarious conditions can mean we receive lower wages and, subsequently, lower super contributions. And with 3 in 4 part-time workers women, it’s no wonder we’re retiring with 30% less super than men.

Has COVID-19 changed this?

Over the past few months, more of us have been working from home than ever before. Whilst having the capacity to work from home is a privilege that not all of us share, recent research of Australians’ work habits during COVID-19 has revealed some interesting insights.

A recent survey from the Australian Institute of Family Studies looked at how over 7,000 Australians had adjusted to the crisis from May to June 2020. Whilst nearly two-thirds of respondents reported to be working from home (up from just 7% pre-pandemic), the distribution of childcare and housework between parents remained relatively unchanged.

Even a pandemic didn’t shift the gendered split of unpaid domestic work. Pre-pandemic 54% of women were doing the bulk of the parenting (down to 52% during the pandemic), while the portion of couples splitting this work evenly remained relatively unchanged (38% pre-pandemic vs. 37% during the pandemic) and the number of men doing most of the parenting has risen slightly (from 8% pre-pandemic to 11% during the pandemic).

But what did change was the split between paid and unpaid childcare. Paid early education and childcare dropped by almost 25% during this period with 70% of parents now caring for kids while they worked from home. This isn’t the story for everyone but does open an interesting conversation about the impact of flexible work on unpaid care work.

It’s important to note that during this time the government did introduce the Early Childhood Education & Care Relief Package, which increased subsidies and enabled many families to receive free childcare for a 3-month period. However, just a few months later these free childcare subsidies have ceased, with many concerned this ‘snap back’ to old policy will financially cripple already struggling families who are still navigating the impacts of COVID-19. (Read more and sign the petition to Make It Free here, we have!)

Why is this work ‘invisible’?

It’s not news to you, lady, but our economy functions on the systematic exploitation of women’s work, and some women more than others. We are the backbone, and without us, the system would fall apart. But why?

In a patriarchal capitalist society, value is assigned to work with a dollar sign. The invisibility of women’s work stems from the way our society measures our contributions. Unpaid work doesn’t necessarily produce economic output in the same way as paid employment does. The narrow lens used to measure economic activity wasn’t built to include unpaid work, and that was, and remains, a deliberate decision.

Another important part of the story is the harmful gender stereotypes that label domestic work as ‘women’s work’. The way society raises women to act as nurturers and carers paints this work as a gendered responsibility placed solely on the shoulders of women. And these outdated social norms have been weaponised against us to keep this work an unequal and gendered burden.

What is intentionally kept out of sight is the value generated by unpaid work. So, the first step to sparking change is to put this work in the spotlight. Highlighting the economic contribution that unpaid work brings to our economy enables us to factor this work into policy decisions. Putting a dollar figure on unpaid work and starting conversations about the invisibility of women’s work is essential. You can’t manage what you can’t measure, right?!

What needs to change

Clearly, a lot needs to change when it comes to unpaid work. Both at an individual and a systemic level, the way we recognise and assign responsibility for unpaid work must change to improve outcomes for women across the board.

The Australian Human Rights Commission specifically looked at the link between unpaid caring work and women’s retirement prospects. Their 2009 report came back with three key strategies to help elevate women’s long-term financial outlook, including:

Reducing barriers to women’s participation in paid work to close the gender pay gap, such as increased affordability of childcare;

Investing in ways to redress women’s disadvantage in super schemes;

Recognising and rewarding unpaid care work in retirement income systems.

In order to redress the inequality and invisibility of unpaid work, we need to challenge the gendered stereotypes and tropes that cause this work to be unevenly distributed at home and in society. This means actively challenging the gendered roles of men as the ‘breadwinner’ and women as the ‘caregiver’. Lady, this means having open and honest conversations with your family and household about sharing the burdens of household duties and care.

But it also requires the support of employers in helping to enable the redistribution of unpaid work. This means championing family-friendly and care-friendly working conditions (such as flexible work hours, job sharing and enabling working from home arrangements) that increase women’s participation in the paid workforce.

And speaking of social norms, we need to actively challenge and dismantle harmful gender stereotypes for men as well. This means normalising men’s caring roles to enable a more equal distribution of this work which would enable them to share the burden without emasculating or punishing them. And this means increasing flexibility for men at work as well to make the shared responsibility of care work a viable reality.

In our view, it’s about starting conversations. Nothing changes unless we start a dialogue about what isn’t working for us, and putting words to what an alternative vision might be. This means talking to your partner, parents, grandparents, Elders, housemates, family members, and bosses about how to make work work for you. It can be an uncomfortable conversation to start, but the cost of staying silent is too big to ignore.

Do you have any questions or comments about unpaid work that we didn’t cover here? Let us know! Get in touch with us via → hello@ladiestalkmoney.com.au